Fraud Management & Cybercrime , Next-Generation Technologies & Secure Development , Ransomware

Massive Malware Outbreak: More Clever Than WannaCry

Rapidly Spreading 'Petya' Malware Variant Has an Appetite for Destruction

The second global outbreak of file-encrypting malware in as many months sees cyberattackers having designed potent, rapidly spreading malicious code far faster than organizations have been shoring up their defenses.

See Also: The Gorilla Guide to Modern Data Protection

On Wednesday, computer security experts were analyzing how ransomware - an apparent variant of previously seen malware known as Petya - first struck organizations in the Ukraine. The malware quickly spread across Europe, Asia and North America, including Russian oil producer Rosneft, a Cadbury chocolate factory in Tasmania and global shipping giant Maersk (see Another Global Ransomware Outbreak Rapidly Spreads).

Microsoft said Tuesday that it had seen infections affecting more than 12,500 machines in 65 countries.

"The new ransomware has worm capabilities, which allows it to move laterally across infected networks," Microsoft says. "Based on our investigation, this new ransomware shares similar codes and is a new variant of [Petya]. This new strain of ransomware, however, is more sophisticated."

The new Petya variant includes clever improvements on WannaCry, the ransomware worm that began attacking Windows systems on May 12, ultimately spreading to 300,000 machines. For example, whoever created the latest version of Petya apparently revamped it with new capabilities that allow it to infect even up-to-date Windows systems running the latest software patches.

"Ransomware is now evolving faster than our responses to it," writes Mark Pesce, an inventor and futurist, on Twitter. "No points for guessing what that portends."

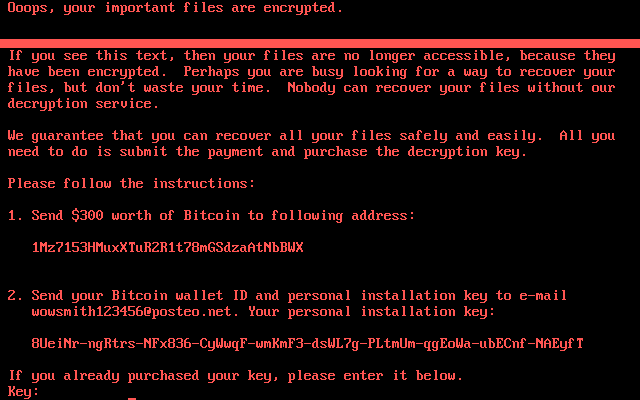

Like most other forms of crypto-locking ransomware seen today, once Petya infects a PC, it will encrypt the entire hard disk. This variant then demands a $300 payment in the virtual currency bitcoin. On the surface, it seems the attackers are seeking financial gain.

Similar to WannaCry, however, Petya's developers didn't design a robust system to pay the ransom. In fact, the ransom aspect may just be a red herring to disguise the real goal of sowing chaos, says Nick Bilogorskiy, senior director of threat operations at Cyphort.

"That's the weird thing about this," he says. "[Petya] really leaves the machine in an unstable state. It seems to be a lot more damaging than typical ransomware attacks."

Petya seems to be engineered to create a mass number of infections and create widespread damage, says Nick Savvides, Symantec's head of strategy for Asia-Pacific and Japan. That could mean the attackers are actually doing something else, using Petya as a distraction.

"It's a technique that has been used before," Savvides says. "It would not surprise me if that's the case. Right now, it's too early to say."

MeDoc, You Infected

In Ukraine, it appears organizations were initially affected after downloading a malicious update for accounting and invoice software called MeDoc, according to a blog post from FireEye. Short for My Electronic Document, MeDoc is made by a Ukrainian company of the same name.

Numerous Ukrainian organizations - including the country's central bank, government agencies and Kiev's Boryspil Airport, among other victims - were hit with the Petya variant.

Launching the attack via MeDoc would have been elegant, in that it's a must-use piece of software for many Ukrainian organizations, according to the operational security expert known as the Grugq. "Everyone that does business requiring them to pay taxes in Ukraine has to use MeDoc (one of only two approved accounting software packages). So an attack launched from MeDoc would hit not only Ukraine's government but many foreign investors and companies," he says in a blog post.

Slipping malicious code into a software update remains a highly effective but relatively rare type of attack. Companies vigilantly guard their source code against such as attacks. To pull it off, attackers would have to gain access to a company's system and then tamper with the source code without being detected. Software updates are cryptographically signed, so versions that have been tampered with would likely somehow have to have been installed without tripping security alarms.

Multiple security firms see MeDoc as the initial infection vector, at least for organizations in Ukraine. "Microsoft now has evidence that a few active infections of the ransomware initially started from the legitimate MEDoc updater process," the company says in a technical analysis. "As we highlighted previously, software supply chain attacks are a recent dangerous trend with attackers which requires advanced defense.

Regardless, the Ukrainian government and multiple security firms have reported also seeing the malware spread via phishing emails with malicious attachments containing Petya that pretend to be resumes or delivery notices.

SMB, Exploited Again

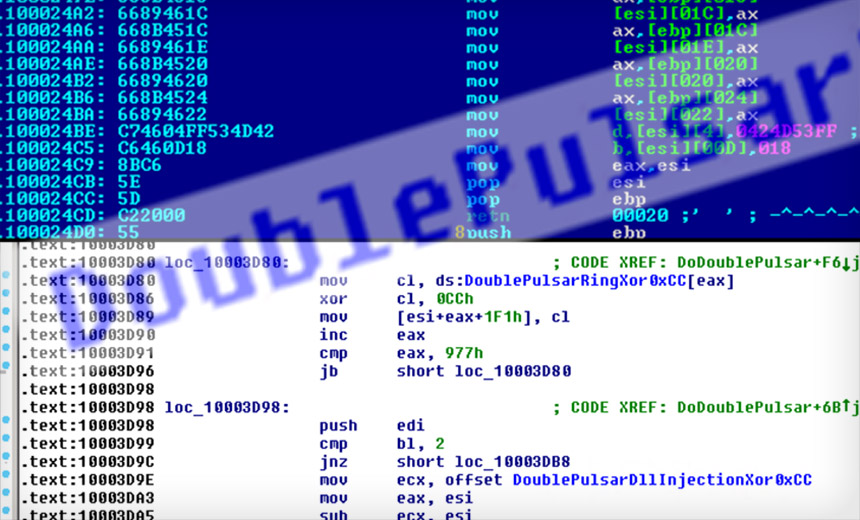

Like WannaCry, Petya uses an "EternalBlue" software exploit for Microsoft Windows, which security experts believe was built by the U.S. National Security Agency. WannaCry rapidly spread by scanning the internet for Windows computers vulnerable to the EternalBlue exploit, which targets a server messaging block version 1 file-sharing protocol (see WannaCry Ransomware Outbreak Spreads Worldwide).

The Shadow Brokers, a mysterious group that somehow acquired a large batch of these "Equation Group" exploits and tools, leaked the exploit in April. Microsoft patched the SMB vulnerability in March in its supported systems, a month prior to it becoming public. At that time, it also patched another SMB flaw, CVE-2017-0145, that had been targeted by an Equation Group exploit tool called EternalRomance.

After WannaCry appeared, Microsoft also issued emergency patches for three operating system out of "mainstream support," including Windows XP.

WannaCry Writing on the Wall

Many organizations, however, appeared to have not patched the SMB flaws targeted by WannaCry, and it quickly became the largest and fastest ransomware attack on record. Since then, both U.S. and U.K. intelligence agencies have said they believe hackers backed by North Korea created it.

In theory, WannaCry should have served as a wake-up call for organizations that the widespread SMB flaw could - and no doubt would - be targeted again by enterprising attackers.

"I'm as disappointed as probably the rest of the world is that there's machines out there that are still being impact by this exploit," says Tim Wellsmore, FireEye's director of threat intelligence for Asia-Pacific, in a phone interview.

But Petya apparently has adapted itself to wreak havoc even there is a narrowing opportunity to attack machines vulnerable to the NSA exploit.

Credential Snagging

The variant of Petya that's been infecting systems since Tuesday offers at least one major improvement over WannaCry: it doesn't only rely on computers that are vulnerable to EternalBlue to spread. Several security vendors say the malware can also employ legitimate Microsoft tools to spread.

Once on a machine, Petya collects login credentials stored on a computer in order to gain access to other systems, Cisco's Talos intelligence unit writes in a blog post.

That move is "a natural escalation of ransomware," writes British security researcher Kevin Beaumont on Twitter.

Yep automating lateral movement with credential stealing is golden. It's a natural escalation for ransomware.

— Kevin Beaumont (@GossiTheDog) June 27, 2017

Once Petya has collected login credentials, it uses PSExec, a Microsoft remote access tool that's similar to telnet. The tool allows a user to remotely access an application on another computer. Petya plugs the login credentials it's pilfered into PSExec and tires to infect other machines.

Security experts say Petya also employs a Microsoft tool set called Windows Management Instrumentation - used for managing fleets of Windows machine - to try and spread.

Such use of legitimate tools by hackers can be difficult to detect, although the security industry has been developing software to try to spot signs of suspicious behavior.

The leaps hackers take across systems using legitimate tools is often referred to as "lateral" movement, and unleashing ransomware with the ability to do this is bad news for enterprises.

"This is the power of lateral moves [with] authenticated access," writes Nicholas Weaver, a computer science lecturer at the University of California at Berkeley, on Twitter. "Worms [without] 'vulnerabilities' are still catastrophic."

Mysterious Motivations

Like WannaCry, Petya only offers one, hard-coded bitcoin address for paying the ransom, says Nick Bilogorskiy, who leads threat operations at anti-malware startup Cyphort.

The sole bitcoin address is unusual because ransomware attackers usually distribute a different address to each victim, in part to keep track of who has paid and more easily automate the process of sending them a decryption key.

Also, only one email address was offered to victims to communicate with the hackers. The German company that runs the email service, Posteo, says it has already shut that account down. That means those who do pay would unlikely see their files decrypted.

"You can't really pay," Bilogorskiy says. "I wouldn't recommend trying."

Appetite for Destruction

Instead of creating a robust payment system, it appears that attackers have instead focused on destruction and spreading chaos.

Once Petya infects a machine, it starts encrypting some files. After a reboot, the machine then encrypts all system files, including the Master Boot Record, or MBR.

"Not only is your data encrypted, but the entire partition is encrypted," Symantec's Savvides says.

The MBR is first sector of a hard drive that the computer looks to before loading the operating system. Tampering with the MBR can have a devastating effect on a computer, and other types of malware have sought to corrupt it, resulting in a bricked machine. Such MBR tampering was also spotted last year in an earlier version of Petya by anti-virus firm Kaspersky Lab.

But the inclusion of that kind of destructiveness "just seems to be a lot of work," Bilogorskiy says. "Cybercriminals usually don't take that much time to code something. This to me feels a lot more complicated."

Update (June 28): Updated to note that an apparent mea culpa issued by MeDoc Tuesday in a website statement written in Russian - "Attention! Our server made a virus attack. We apologize for the inconvenience!" - was a mistranslation by Google Translate. In reality, the company was warning that its servers were under attack.

Executive Editor Mathew Schwartz also contributed to this story.