Data Loss Prevention (DLP) , Fraud Management & Cybercrime , Governance & Risk Management

Marriott: Breach Victims Won't Be Forced Into Arbitration

Victims Objected to Terms Of Fraud Monitoring Agreement

There's often been a cheeky devil in the details when data breach victims sign up for free fraud-monitoring services from breached organizations: In return for accepting one year of prepaid identity theft monitoring, consumers must often waive their right to join class-action lawsuits or pursue other court actions against a breached business.

See Also: 2017 Security Predictions from Malwarebytes; New Year, New Threats

Just such a situation arose last year with Equifax, which on Sept. 7, 2017, disclosed that it had suffered a massive breach that it eventually found had compromised data for at least 148 million people in the U.S., 15 million in the U.K. and about 20,000 in Canada (see: Equifax Breach 'Entirely Preventable,' House Report Finds).

To get signed up for Equifax's fraud-monitoring service, TrustedID, consumers had to agree to an arbitration clause. The inclusion of the clause, however, caused outrage, with lawmakers and attorneys general promising to crack down. Under fire, Equifax eventually removed the offending terms of service, later in September 2017.

Following Marriott International's disclosure of its data breach, this situation appears to be happening again. But according to documents filed in federal court in Maryland on Tuesday, Marriott - like Equifax - now appears to be backing away from what breach victims, and their attorneys, say are the onerous conditions under which the company is offering fraud monitoring to victims of a breach that Marriott failed to spot, and which ran unchecked for four years.

Plaintiffs Call Move 'Underhanded'

Marriott's breach exposed up to 500 million accounts for customers of its Starwood line of hotels, which include brands such as W, Sheraton and Westin. The breach, which affected the Starwood guest reservation database, started in 2014 and ran through Sept. 10, 2018 (see: Marriott's Mega-Breach: Many Concerns, But Few Answers).

The breach was one of the largest such incidents to have come to light this year, and exposed a significant amount of personal information. For 327 million accounts, the breach exposed a combination of name, postal address, phone number, email address, passport number, birth date and travel data. For some of those accounts, encrypted payment card numbers and expiration dates were also exposed, as was potentially the information attackers would have needed to decrypt the payment card data. For the other 173 million accounts affected by the breach, the information exposed was limited to name and sometimes other data such as mailing address, email address or other information, the hotel giant reports.

As is customary, it didn't take long for a class-action complaint over the breach to emerge. On Dec. 6, a breach victim filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court in Maryland that alleges that the hotel giant has put people at risk of identity theft. The complaint seeks unspecified damages.

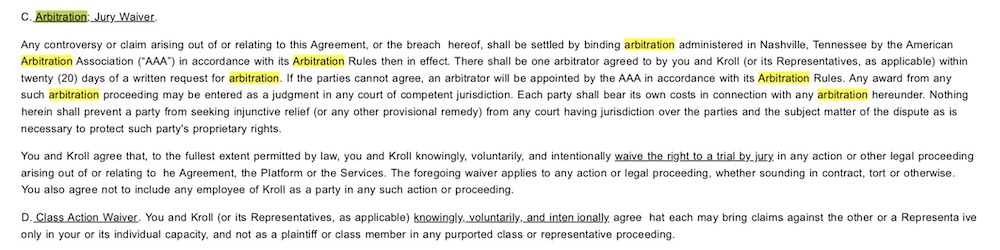

Marriott is offering all breach victims a one-year, prepaid subscription to WebWatcher, a fraud-monitoring service offered by risk consultancy Kroll. But the lawsuit contends that the terms and conditions for using WebWatcher mandate that disputes go to mandatory arbitration and that by signing up, consumers forfeit their rights to jury trials or class actions. In other words, from a legal-rights perspective, the service would hardly appear to be "free."

From the complaint: "Marriott engaged in an underhanded attempt to induce putative class members to waive and limit their legal rights, creating both uncertainty about whether to accept the WebWatcher product and whether they were still permitted to pursue legal claims in court through a class action vehicle," the plaintiffs allege. "The net result of this conduct is dissuading consumers from taking all steps to vindicate their rights."

Forced Arbitration: Illegal, Sometimes

Now, however, it appears that Marriott is backing off those terms and conditions. In recently filed court documents, Marriott says it doesn't intend to enforce those terms upon WebWatcher subscribers.

"It's pretty significant - and rare - for a company to agree to this," according to a spokeswoman for Edelson PC, the law firm that filed the class-action complaint.

A declaration filed by an Edelson attorney says that Marriott has "clarified and confirmed" that the terms of the WebWatcher agreement would not apply to "putative class members."

A Marriott International spokesman says the company doesn't comment on pending litigation and didn't answer a question about whether it has yet revised the terms and conditions that breach victims are signing if they enroll with WebWatcher. Kroll officials couldn't immediately be reached for comment.

But forced arbitration and the banning of court actions have historically been one strategy that organizations - and especially financial institutions - have employed to try and reduce their legal exposure. The practice, however, has been criticized for limiting what have been customary legal rights for consumers to seek redress.

How did we get here? A series of Supreme Court decisions previously paved the way for arbitration clauses, which were shaping consumer litigation, writes Matthew H. Adler, a partner with Pepper Hamilton LLP, in an October 2017 blog post.

"No courts, no massive suits - just individual versus business on a single issue and contract," Adler writes.

Although organizations such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce support arbitration, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau created a rule that banned financial services companies from using arbitration clauses in order to prevent consumers from pursuing legal action as a group.

The CFPB rule became law on Nov. 1, 2017. But companies outside of the financial services sector are still allowed to use arbitration clauses.