Cybercrime , Encryption & Key Management , Enterprise Mobility Management / BYOD

Dutch Police Bust 'Cryptophone' Operation

Another Secure Service - As Allegedly Marketed to Criminals - Fails to Deliver

Once again, a supposedly secure service allegedly marketed to criminals has proven to have limits.

See Also: ISO/IEC 27001: The Cybersecurity Swiss Army Knife for Info Guardians

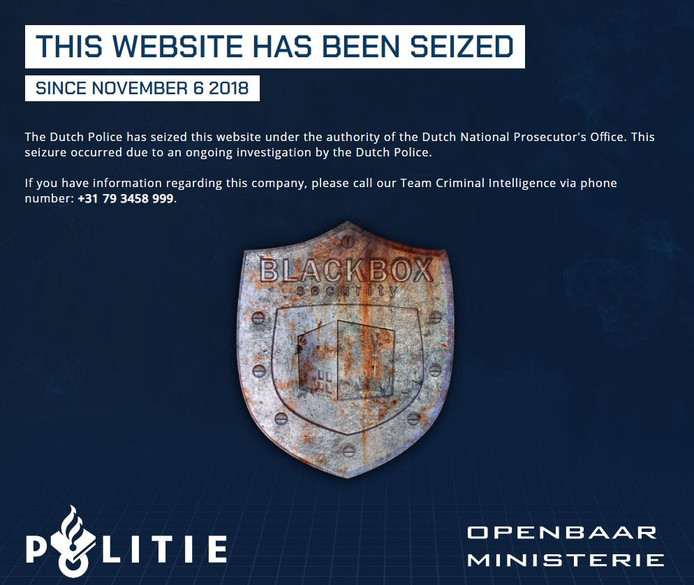

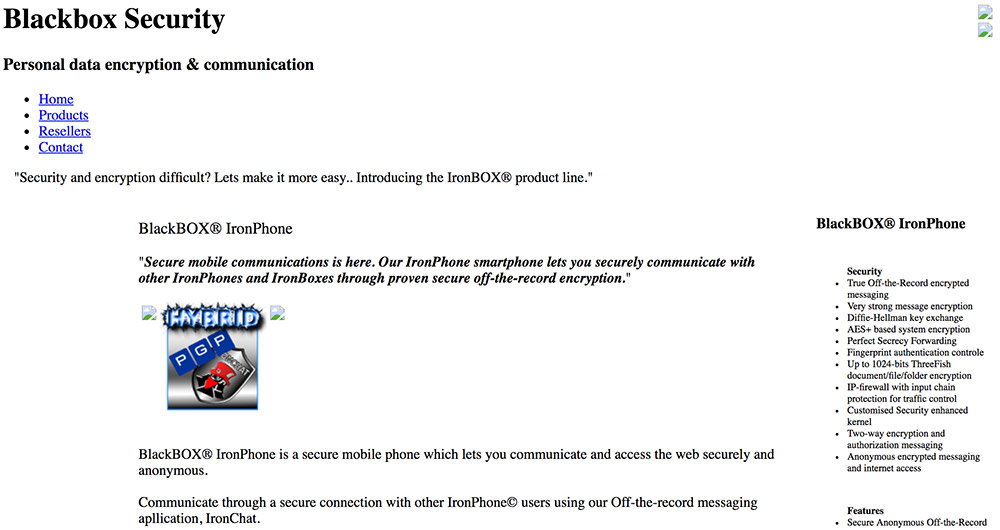

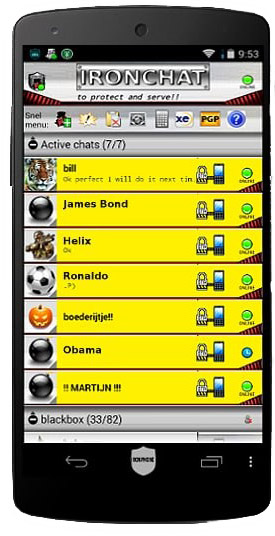

Encrypted messaging handset provider BlackBox's supposedly secure communications network was dismantled after Dutch police seized its server. The operation also allowed the cops to read more than 258,000 encrypted chat messages sent by users of BlackBox IronPhones, which used a customized version of OTR Messaging - for off-the-record - called IronChat to supposedly offer end-to-end encryption for messages.

Dutch police say they discovered the cryptophone operation while investigating an alleged money laundering operation.

Police didn't just shut down the network. Instead, they seized a server and began monitoring the service.

"We had sufficient evidence that these phones were used among criminals. We have succeeded in intercepting encrypted communication messages between these phones, decrypting them and having them live for some time," Dutch police said on Tuesday. "This has not only given us a unique insight into existing criminal networks; we have also been able to intercept drugs, weapons and money."

Police say their investigation has already allowed them to bust a drugs lab in Enschede, Netherlands, and make 14 arrests, including a 46-year-old man from Lingewaard who's suspected of running the cryptophone company, as well as his alleged partner, a 52-year-old man from Boxtel.

Police have also seized €90,000 in cash (equivalent to $103,000) and automatic weapons and drugs, including large amounts of MDMA and cocaine, as well as machines, stamps and labels apparently used for shipping them.

Why Police Revealed Operation

"This operation has given us a unique glimpse into a criminal world in which criminal acts were openly discussed," said Aart Garssen, head of the Regional Investigation Service in the Eastern Netherlands, at a Tuesday press conference.

He said police had decided to reveal their operation to forestall violence, after BlackBox users started to voice suspicions about each other - which police learned about thanks to monitoring the IronChat message traffic - following people being arrested.

"They suspected each other of leaking information to the police," Garssen says. "This mistrust among the users of the phones toward each other can lead to reprisals. Now, we're making it clear that the police intervened [by using] intercepted communications."

Dutch police later issued a follow-up statement, saying the decision to unmask the operation was made, in part, because the reprisals posed an "unacceptable" public safety risk. "Criminal reprisals can affect not only the criminals involved, but also innocent bystanders," it said.

Encrypted App Offering

Police say BlackBox IronPhones looked like smartphones, but with much reduced functionality; they can only send and receive messages and images, and only with other cryptophones. Their supposed security didn't come cheap - subscriptions cost €1500 for six months.

"On the device there is also a panic button via which all data can be deleted at once," police say.

BlackBox's marketing materials claimed that the company's products had been endorsed by National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden. But Snowden has refuted that claim.

There are false reports going around that I endorsed something called "Iron Chat," based on a fraudulent marketing by the company. For the record, I've never done a paid endorsement of any kind, and the projects I endorse tend to be free, like @TorProject, @QubesOS, & @Signalapp.

— Edward Snowden (@Snowden) November 8, 2018

Some Crypto Phone Services Under Fire

The BlackBox IronPhone takedown isn't the first time that police have shuttered a cryptophone service for alleged criminal ties.

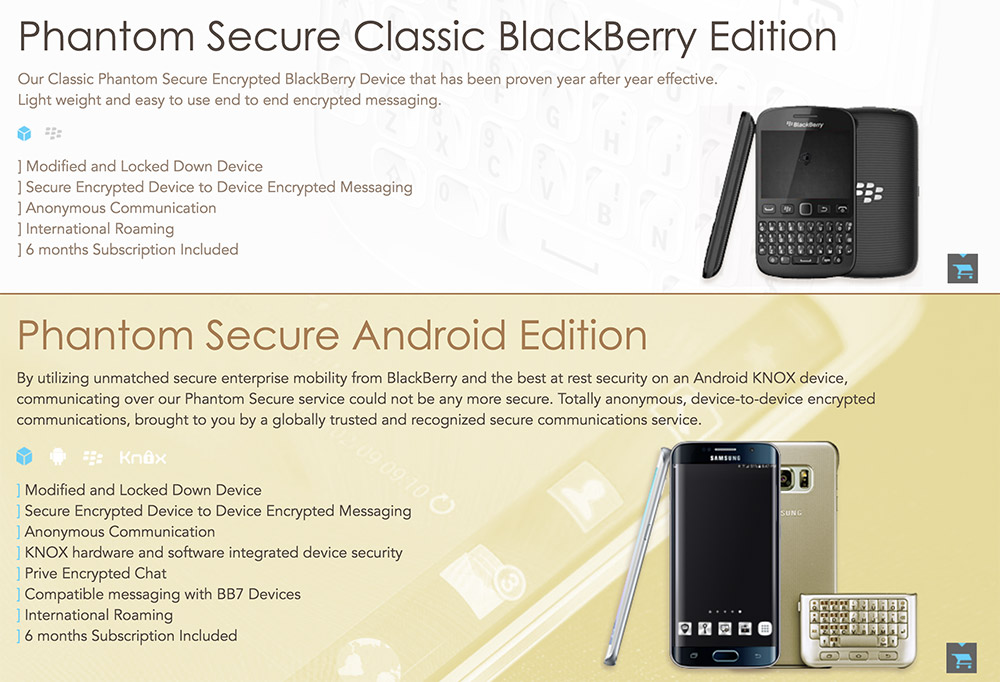

In March, the U.S. Department of Justice charged five individuals with running a secure smartphone service called Phantom Secure that was designed and marketed to help criminals evade law enforcement agencies (see: Feds: Secure Smartphone Service Helped Drug Cartels).

Authorities charged the men with providing the phones to individuals who used them to ship cocaine and MDMA from the U.S. to Australia and Canada. Six-month subscriptions for the devices ran about $2,000 or $3,000. The FBI said users of the service included a known member of Mexico's Sinaloa Cartel.

Phantom Secure purchased handsets from BlackBerry and other manufacturers, then removed "the hardware and software responsible for all external architecture, including voice communication, microphone, GPS navigation, camera, internet and Messenger service," according to a federal complaint.

The Phantom Secure team would then install Pretty Good Privacy encryption software and the Advanced Encryption Standard cipher - for encrypting and decrypting data - on top of an email program, it said. All communications were allegedly routed through virtual proxies and encrypted servers in such locations as Hong Kong and Panama, with the company's marketing materials proclaiming that "Panama does not cooperate with any other country's inquiries."

Points of Potential Failure

Services such as BlackBox and Phantom Secure, if they are marketed to criminals, become an obvious target for law enforcement takedowns. And despite their marketing claims, they may be far from impervious to such efforts.

Even the legitimate VPN service called HideMyAss.com had limits, as LulzSec member Cody Kretsinger learned to his peril in 2011, when the U.K.-based service complied with a law enforcement records request that unmasked Kretsinger's activities. He was jailed for one year in 2013 for hacking Sony Pictures.

The same goes for so-called darknet websites that can only be reached by using the anonymizing Tor browser and which only accept payment in bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies, such as monero.

While all of that would seem to provide a degree of anonymity, authorities have some cryptocurrency-tracing abilities, especially when virtual currencies get converted to cash. In addition, darknet markets, even if they're hosted using bulletproof services, must still be remotely administered. Also, if users buy physical goods, such as drugs, they must be shipped from sellers to buyers, all of which poses an operational security risk (see: Glove Use Key to Arrest of Alleged Darknet Drug Trafficker).

That makes for a long list of potential flaws or missteps for police to exploit.

Tough Times After AlphaBay

Last year, for example, the FBI on July 4 seized darknet marketplace AlphaBay, which processed more than $1 billion in narcotics sales, after identifying its Thai-based administrator, who made multiple OPSEC fails (see: One Simple Error Led to AlphaBay Admin's Downfall).

After AlphaBay went dark, many users switched to rival marketplace Hansa, which processed about 1,000 orders per day, mostly for hard drugs.

Unbeknownst to Hansa users, however, Dutch police had already seized that site two weeks before AlphaBay went dark. As users moved from AlphaBay to Hansa, police watched everything they did.

"The Dutch police collected valuable information on high-value targets and delivery addresses for a large number of orders," Europol, the EU's law enforcement intelligence agency, said at the time. "Some 10,000 foreign addresses of Hansa market buyers were passed on to Europol."

Cybercrime intelligence experts say the dramatic seizures of those marketplaces led many criminals to move to encrypted apps for doing business.

But with police showing that they can infiltrate service providers and sites, eavesdrop on even darknet markets, as well as turn ringleaders into informants, for criminals seeking services that purport to offer anonymity and promise ironclad information security, caveat emptor.